For part two of my examination of the possibility of an ecovillage at the University of Vermont, I thought it would be fitting to talk to some of the people already participating in the school’s residential programs centered about sustainability. On April 11th, I had the pleasure of talking with Walter Poleman, the Director of UVM’s GreenHouse Residential Community. Having previously taken an ecological design course with Poleman, I was well aware of his interests in ecological design and place-based learning, and was eager to learn more about the role of these within the Greenhouse program. Moreover, I wanted to understand GreenHouse’s role in the larger UVM community, and see if Poleman either recognized the community as an ecovillage, or saw potential for growth into that community form. Below is the transcript, copied from my audio notes (Poleman is designated by W.P., and I am designated by S.F.). The beginning of our interview focused on the Greenhouse Program itself, and the latter part on the relationship between the program and ecovillages.

SF: Okay, so my first question is just can you give me a little history on the UVM Greenhouse?

WP: Yes, the building itself was built in 2006. I remember when the vision kind of came out that they were going to build new resident halls on campus for the first time in 30 years, the president at the time Dan Vogel was interested that they be themed residential colleges. And actually the honors college liked that, and now over there it is like a college existing next door. Then a group of faculty and others said “what about if we had themed housing: broad big themes that any students from any major could get excited about being a part of” so the initial ones that started were global village, which is over in L&L… That was the idea that they could unite together the existing houses. Greenhouse was a new concept. There was already Slade, which was already a themed communal housing where people came together, the greenhouse was meant to fill the ideas of “how could a community of people think of how to live sustainably”. The amazing thing, as they were building this LEED certified place, is that we asked ourselves could we design a program to go along to this housing. So, we launched the greenhouse program in 2006 and it has evolved from there. That was the beginning with making a big program available to our students, providing them with an enriching learning environment. So, that is how it began and eight years later it has evolved quite a bit (although a lot of the same structures are still in place) due to student feedback and new faculty and experimenting with new things. Now, ecological design is one of the main themes over here.

SF: Could you tell me a little bit about the specific infrastructure of the greenhouse and what makes it sustainable?

WP: Yea, well the facility itself… the sustainability thinking that has gone into it is energy efficiency so there is a lot of air-exchange type of stuff. Even though it is air conditioned because they wanted to use it for summer housing (a multi-use vision), they wanted to make it very efficient. I can’t tell you exactly what it is but the energy usage for heating and cooling is efficient. The materials, like this table, the doors, a lot of the rock, are sourced locally. The paints and the carpeting (though you can’t tell so much) are low emission kind of materials. There’s a lot of light in general the way that the windows were done, to maximize the use of outdoor lighting too. That’s the building itself, it’s LEED certified so it has gone through all the environmental design criteria. The program itself is (as you’ll know from class with me) designed to feature the place where it is located, and so we look at the community. It is important to be intimate with the building but also with the Burlington landscape and larger landscape so that when you live here the town is your classroom. So we promote that with field trips, lectures, meals from local farms, and other integrated opportunities. That local piece is definitely a part of the sustainability. We try to showcase local sustainability efforts; the other day people from Carshare VT were here trying to get the students to sign up. Again, different speakers related to social justice through sustainability, environmental art, and anything else connected to place have been featured. So, there are two parts to the sustainability: programming and then the facility’s structure.

SF: As for the social environment that is developed within the greenhouse, could you talk about the role of collaboration and living together in creating a sustainable environment?

WP: The idea is to bring together people who are interested in this theme, into a community. But… not let it stop there but look at “what are the community structures”? We have villages embedded within the larger community, guilds which are interest groups around themes, classes, and the hope is that through the application process we will develop as diverse a group as possible. Diversity of majors, race and ethnicity, background: it is partially about “how can we engage with people with other cultures?”

So it is really about embracing cultural diversity, and then how do you bring that together in thinking about “what does it mean to live sustainably”? We aspire to have a community that is very inclusive where difference is celebrated. The reality is that Vermont is not a very diverse place, but that being said we try to make the most of what we do have. For instance, next Wednesday all the housekeepers and other staff are bringing food from some place we feel connected so we will have Korean food, Bosnian food, rural Vermont food too. One guy is going to make bear stew. So, it is really trying to celebrate a diversity and as we talked about in our class, the idea is “what happens when you go to a different culture and landscape? How do you design things that fit there?” And so that is kind of the vision. So we try to create a community where a diversity of people and ideas is engaged.

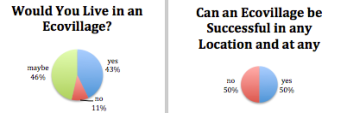

SF: Do you think it is easier for students to live “sustainably” or take on sustainable practices in an environment where the people around them are doing the same thing?

WP: I think so, a lot of people who come here say “I was the only one in the family, or in school that cared”. They often felt like a minority in some way, and when they come here they think, ‘ wow there are so many people here interested in this stuff’. They share with each other and grow off each other. So I think it is easier. It is kind of interesting to intentionally form a community with a common interest, but once the community is together you try to go throughout the diversity within that community.

SF: Do you think that in any way the greenhouse has an effect on the other dorms on campus? Either negative because students interested in sustainability may be concentrated here, or positive in that maybe other people may be prompted to be involved?

WP: There is a little bit of a tension. We aspire to have the ideas that happen here radiate out into the campus. The idea is that we want our place to be a strong a point of service in the community. We want to serve the greater UVM and Burlington community. But, it would be interesting to ask people that. Anytime you sort of designate something it can become sort of exclusive feeling, which is sometimes the danger, and I think that your question is a really good one. If there were no greenhouse all these people would be living elsewhere and maybe they would be having positive impacts on other locations.

SF: It is kind of hard to gauge because the learning they gain here and the growth they gain here working with other people they may not get if they were dispersed in the larger environment, but by being dispersed they could perhaps pass their knowledge to different demographics.

WP: And this is only a 2-year program so our hope is that students can learn here and form good friendships, and then when they move on, they can bring those lessons with them. I’d like to think these ideas radiate outward over time.

SF: Do you think the high turnover of people in the dorms every year really adds rejuvenation and a new face to the project as time goes on?

WP: Definitely, I think it is healthy. In fact we try to model the program like an ecosystem: there are always new people and ideas regenerating. That is really healthy. But, some programs are all new students every year –a freshman program- but here we try to have a two-year experience. As a second year student in the greenhouse you often get the opportunity to act as a mentor to first year students. Our understanding is this does happen: the place develops, and second years really feel they have an opportunity to give back.

SF: On the opposite side of the spectrum, I know last year there was a “yo-guild” (yoga guild), and I saw a sign for it right outside today, so obviously it is still here. Is it hard to maintain stability in the program when the people are constantly changing?

WP: That is a perfect question for today because I just talked to the yo-guild leader today, Jackie. She has identified a new person who will take her place next year. That is the beauty of the overlap here, if you have a healthy program in place there is that combination of getting to play a leadership role when new people come in, but also take advantage of their ideas.

SF: As I mentioned my project is on eco-villages, so I am just curious how you would define an ecovillage, and if you believe the greenhouse could be considered an ecovillage of sorts.

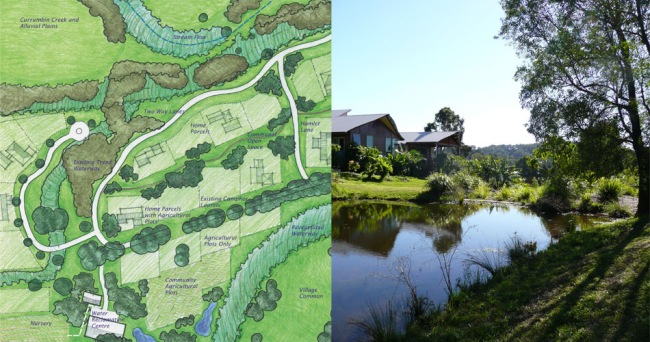

WP: Well, I have certainly encountered some ecovillages. There are some in VT and Ithaca where I am from (it is actually called “ecovillage”) and the idea really I think is that people can inhabit a place and within the community there is a higher degree of self-sufficiency. It is very community intentional and community engaged. In terms of the higher self-sufficiency, it might have to do with growing your own food, generating your own energy…etc. We don’t really do that at all here. We could, some college dorms definitely do it. So I would say that the intentionality of the programming (being mindful about food consumption, waste, opportunities to teach and learn) matches the mind of an ecovillage: we are an ecologically designed village. It is as much about community as it is about sustainability.

SF: Do you think the greenhouse fits the “mold” of an ecovillage within the restraints of the university community?

WP: You mean how far could we go down the line to create a village? I think slade is a lot closer in that they are more community-scale, whereas we are still really dorm based. Moreover they are actively looking at cooking, feeding, sourcing their food together –that is a huge, huge step in the right direction-, and I know right now they are not going to be in their building next year but from what I understand (from Deane Wong and a bunch of other design forces), the students are getting an opportunity to play a role in the re-design. So, anyway, they are closer to that than us, because of their relationship with self-sufficiency. Many of our students move onto there though, so we are kind of a nice feeder place for that.

SF: What is your role?

WP: A lot of cross-departmental things, as a faculty member is needed and I am in charge more or less of the curriculum. I manage a lot of different things, there is large staff, a program coordinator, then there is a program specialist, then there are students with leadership roles… So I am kind of directly responsible for all of those folks.

SF: Could you tell me a little about the current projects that are going on in the greenhouse?

WP: The big one, from my perspective is the ecological design collaboratory. Greenhouse is at the center of that. How do we grow this idea of the collaboratory, is the main thing for me. We will be doing a lot of courses in the summer; there is lots of community education… so that is a big example of a project. Related to that is another program called ecological citizenship which all the second-year students enroll in. it isn’t a big class, rather it includes small classes with skill-based education. With me, they make maple sugar (tapping trees, inventorying the forest…) that is a typical one. There’s also photography, bike repair, woodcarving, furniture building, very hands-on things. They are all related to ecological design.

SF: What do you think makes the greenhouse program so successful?

WP: I think it is adding something of value to UVM. I think the theme, what makes it successful it is open to anybody. It is not just for people in environmental studies, it is meant for engineers, historians, business majors… you name it! This theme of place is really about the whole picture: everyone is related to it. The question is how can we live well in this place and how can we bring our interests and background experience –particularly our academic learning- to this place. That kind of vision fosters success. But the students who come to UVM are what make this program really cool. There is an unpredictable aspect, a lot of the things we get out of the program come right from the students and that is the beauty of it.

-SF